The David Whitney Story

Part II – Chapter 4

Returned to Vermont

Burial at Brookfield

Alonzo Whitney's body was returned to Brookfield for burial in East Hill Cemetery, where his parents were later buried. A large monument marking Alonzo's grave still stands today in honor of his service to his country in its only internal war suppressing rebellion.

Monument to Alonzo B. WhitneyEast Hill CemeteryBrookfield, VT

Photo by Thomas Lee Eichman

On December 16, 1864, a 26th Regiment staff officer, Major Ira Winans, received Alonzo's personal effects from the Regiment Chaplain, Benjamin Franklin Randolph.

Randolph was an African-American but had been born a freeman in Kentucky. He had studied at Oberlin College in Ohio and became the only black commissioned officer in the 26th USCT. After the war, Randolph returned to South Carolina with the Freedmen's Bureau, was elected State Senator for Orangeburg County, and served as state chairman of the Republican Party in South Carolina. While campaigning for election in October 1868, he was assassinated by the Ku Klux Klan in Abbeville County as he stepped from a train.

Included among Alonzo's belongings that Chaplain Randolph had secured were a wallet containing 30 cents postage currency, a money order to the Paymaster P. Edwin Dye, Captain of C Company, signed by Joseph B Mason, Company Sergeant of Company C in the amount of $25.00, to be paid to the bearer and deducted from Mason's pay, two 3-cent postage stamps, a small porte-monnaie, a small knife, and a check on the Assistant Treasurer of New York, drawn by Captain Dye, to be paid to the order of Amanda Williams.

An Unfulfilled Dream—A Wish—Perhaps a Promise

Probably few, if any recruits go off to war without having plans or developing plans for what they will be doing after the war. Alonzo Whitney was no exception, apparently having had such plans, or at least a dream, even a wish for what might lie in the future.

Before Alonzo left the 10th Vermont Infantry Regiment to become, like his brother-in-law, a white officer in a Union-organized, African-American unit, he was detached from Company G—where he had been an infantryman—and was assigned temporarily to another element. From August 1863 until the end of February 1864, Alonzo performed other duties involving skills he had become informally familiar with as an infantryman.

These new duties were foretold in Alonzo's letter to the Coolidges a year earlier. As he reported to Mrs. Coolidge in the fall of 1862 from the 10th Regiment's Potomac encampment, he had been acting as a nurse, caring not for wounded—as they had not yet engaged the enemy—but rather for his many comrades who were sick due to conditions in the camp. Alonzo recalled that Mrs. Coolidge had suggested he consider becoming a physician, and he had mused that by the end of the war—since he had already become a de facto nurse in the camp—he might need little study to take up the practice of medicine.

Now, a year later, Alonzo was formally attached to a field hospital where he served as a nurse for seven months, assigned as a hospital attendant. Maybe his dream was turning into a promise.

A Civil War Field Hospital

Image from Library of Congress Collection

A Mystery?

Why Alonzo left his duties as a nurse to become an officer with the U. S. Colored Troops is a good question, but less than a mystery. In his letter to the Coolidges, Alonzo pledged himself to patriotic duty, which could include dying for his nation if that would help restore peace. Perhaps that sense of duty overrode his plans for a future in medicine.

If Alonzo's motive for leaving his field practice as a nurse was to contribute to the struggle for preserving his country by voluntarily leading freed African-Americans into battle, then he was furthering a long-standing tradition of concern by Vermont's white citizens for the status of their black brethren. Vermont entered the Union in 1777, not as a former colony but as a separate republic, with a constitution firmly proscribing slavery. The state also adopted universal male suffrage with no distinction between the voting rights of Whites and African-Americans.

During the Civil War, at least 150 Vermont citizens of African-American origin served in all-black units, many in the very first such northern unit organized, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. This unit served in the same area of South Carolina as Alonzo's 26th Regiment and gained glory in combat early on in a frontal assault on Fort Wagner on Morris Island, part of the Confederate defenses near the entrance to Charleston Harbor. In that battle, despite heavy casualties, the 54th proved to the nation and the world the valor of black soldiers in general and the men of that regiment in particular. The 54th Massachusetts Regiment's story has been told in the 1989 motion picture "Glory".

Still a Mystery

One mystery concerning Alonzo's post-war plans, however, does remain. In addition to the money, postage, and checks that the 26th Regiment's chaplain found among Alonzo's possessions, there was one very personal item Alonzo had been carrying with him: a gold locket containing the picture of a young lady and a lock of hair. Who this young lady was, and what she meant to Alonzo's future, is, and probably will forever remain, a mystery.

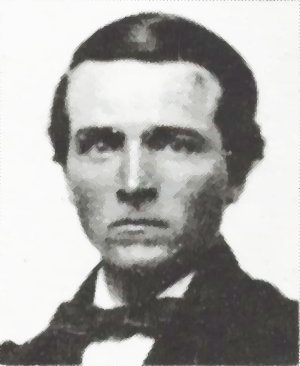

Alonzo B. Whitney

July 1, 1840, to December 5, 1864

Photo from Family Treasuresby David Day Whitney, Alonzo's nephew

©2007 by Thomas Lee Eichman. All rights reserved.