The David Whitney Story

Part II – Chapter 5

David's Military Service

Section 10

Back North to Maryland

"The Battle that Saved Washington"

A Possible Threat to Washington from the North

In the aftermath of the Overland Campaign, while the Union Command was concentrating on efforts establishing positions around Petersburg, the Confederate Command sent a force of at least 15,000 troops into the Shenandoah Valley in the western part of Virginia to clear Union forces from Lynchburg and Lexington and open a path north into Union territory in Maryland. The possible targets of this northern offensive were the port city of Baltimore and the Union's capital, Washington, DC. Both cities had been left with minimal defenses since the start of the Overland Campaign.

A strategic Maryland location on the Confederate path north was the city of Frederick, at which converged the Baltimore Pike/National Road (now Maryland Route 144) leading to Baltimore and the Georgetown Pike into Washington (also called the Washington Pike, now Maryland Route 355). On the Baltimore Pike, a stone bridge known as Jug Bridge crossed the Monocacy River east of Frederick. A few miles south, a wooden, covered bridge across the river was part of the Georgetown Pike, the best route south to Washington. In addition, very near the covered bridge was a railroad bridge on the Baltimore and Ohio line (now the CSX) into Baltimore. On the river's west bank was the B&O's station at Monocacy Junction.

The railroad line extends from Frederick southward toward the Potomac River and then follows the river westward to Harper's Ferry at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. In early July B&O employees alerted the Union Command to the Confederate advance towards Maryland, and one element of the Union's 6th Corps, the 3rd Division, was sent to Baltimore while the rest of the corps followed later, but to Washington.

On Wednesday, July 6, 1864—the same day the last Confederate troops were completing crossing the Potomac into Maryland at Shepherdstown, West Virginia—the 3rd Division marched from their position south of Petersburg to City Point (now Hopewell, Virginia) on the James River. There they boarded steamers that took them downriver to the Chesapeake Bay and on up to Baltimore Harbor.

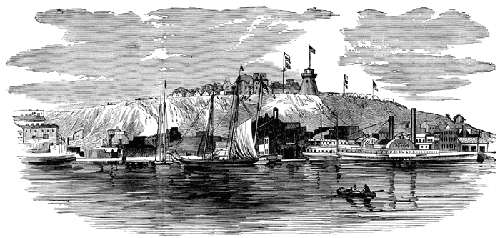

Federal Hill on the South Shoreof Baltimore's Inner Harbor

Image from FCIT Clipart Collection.

The men enjoyed the water voyage as a cool, refreshing relief to the marching and fighting they had been doing since early May. Some even took advantage of the ride to clean their clothes, by stringing them on lines in the water behind the vessels they were on.

Late in the afternoon of July 7th, the first steamer arrived in Baltimore carrying David Whitney and his 10th Vermont Regiment comrades as part of the 3rd Division. Around midnight they, along with a New Jersey Regiment, were loaded into crowded cattle-cars and rode the B&O line west to Frederick, arriving there about 9:00am on July 8th.

Maintaining and Simulating Defenses at Frederick, Maryland

Waiting in Frederick for the arrival of these experienced combat veterans was a force of about 3,000 men made up of home guards of Baltimore, some militia, and various short-term new enlistees, none of whom had yet faced enemy fire. These troops had been moved to Frederick to prepare for putting up the initial defense against a Confederate onslaught on either Washington or Baltimore.

Also very near Frederick, approaching from the west at Middletown, was the bulk of Confederate forces. Part of the Confederate forces had set fires in Williamsport, Maryland, and, as they moved east towards Frederick, extorted a ransom from Hagerstown of $20,000 plus a large amount of clothing under the threat of destruction to that city. They also subsequently got an even more substantial ransom of $200,000 from the city of Frederick.

When David Whitney's regiment arrived on the east side of Frederick, they were immediately deployed in a deceptive maneuver, marching back and forth all day and setting up mock defensive positions in the hills of eastern Frederick in plain sight of the Confederates waiting in the Catoctin Mountains west of the city.

Later that day, July 8th, when Confederate cavalry started streaming into Frederick and a large contingent of Confederate infantry moved south of the city toward Buckeystown, the Union Command concluded that the Confederate Command was apparently preparing an offensive against Washington. It was time to move Union troops south of Frederick to defend the bridges on the Monocacy River and attempt to block the Confederates' passage.

For many of the men of the 10th Vermont Regiment, this was a return to a familar site, as they had been assigned there just a year previously, in early July 1863, to guard the strategically important Monocacy Station railroad bridge as part of the defense of Frederick during the Battle of Gettysburg. David Whitney was not a part of the 10th Regiment at that time, having experienced that great battle much closer up as a member of the 15th Vermont Regiment. However, in the current effort, David was retracing the path of his brother Alonzo and brother-in-law Alpheus Cheney, who had preceded him as members of Company G of the 10th Regiment in the Gettysburg-related defense along the Monocacy.

Repositioning along the Monocacy

By the time the Union troops were ready to leave their positions in the eastern part of Frederick and move down along the Monocacy, Confederate forces were blocking the most direct route. As a result, the Union Command ordered a march eastward for a few miles on the Baltimore Pike and then across farm fields and through woodland to a position across from the rail station, which they reached by midnight that night.

On the morning of July 9th, David Whitney's 10th Vermont Regiment took up their battle position at the very south end of the Union defense line that stretched three and a half miles along the east bank of the river from the stone bridge at the north across the railroad and on to just below the covered bridge on Georgetown Pike. The east bank offered the advantage of higher ground from which to fire on advancing foe. Deployed on the west bank in the vicinity of the railroad terminal was one detachment made up of 200 inexperienced Maryland home guards augmented by 75 men from the 10th Vermont Regiment and led by a 10th Vermont Infantry Company First Lieutenant.

Standing Ground at the Monocacy

In the meantime, the Confederate Command had found a fordable point on the river about a mile and a half south of the bridges. Confederate cavalry used that route to cross and move back upstream to attack the Union defenders in an attempt to drive them away from the bridges. The Union forces managed to hold off this attack, repulsing the initial assault and two subsequent follow-up assaults by the dismounted Confederate cavalry. The battle here lasted from late morning until around 2:00pm, with both sides taking heavy losses. The 10th Vermont Regiment was in the thick of battle because of their position at the southern extreme of the Union line behind the fences of the private farmland through which the Confederate charge came.

This attack was followed by a Confederate infantry division crossing the same ford and moving under cover of the woods along the east bank to face off against the Union's 3rd Division units. The Union Command repositioned its line along the Georgetown Pike with the 10th Vermont Regiment pulled back to a protected position on the Georgetown Pike but again at the exteme southern end of the Union formation. The Union Command concentrated its meager number of artillery guns at this point and ordered troops from the west bank to support this defense by crossing the wooden bridge and then burning it to prevent the Confederates from using it.

Beginning around 2:30pm, the overwhelming number of Confederate forces inflicted great damage on the smaller Union defense but also suffered many casualties in return, as the tenacious Union soldiers, experienced in the combat of the Overland Campaign, refused to give ground.

David's 10th Regiment was again at the extreme left of the Union line and, despite the heavy onslaught of Confederate troops, managed to maintain their position by lying low and holding its fire until the attacking soldiers were within easily visible range. Subsequent assaults by the Confederate forces, however, left the Union position untenable, and around 4:30pm the Union Command ordered a withdrawal of all their forces along the Baltimore Pike to reassemble to the east in New Market, Maryland.

Leaving the Monocacy

As the furthest down the Union line of defense, David and most of his 10th Regiment comrades were almost the last to receive orders to leave their position. By the time they pulled out, the route along which the other Union troops had preceded them in the retreat was blocked by Confederates. To escape, David's unit had to climb a high fence and proceed on high ground through a cornfield making them vulnerable to Confederate fire. Under a hail of whizzing bullets, they scrambled over the fence, weaved their way through rows of corn, and ran around a hill and through an orchard to the B&O railroad track. They then marched along the track until they came to the Monrovia station, just a few miles south of New Market.

At Monrovia the 10th Vermont found a train engine with a string of empty cars, which they commandeered and rode to where the track crossed the Baltimore Pike east of New Market. They waited there for the rest of the Union forces that had assembled in New Market to come and join them on the way back to Baltimore. When the other troops arrived that night, they were surprised to see the 10th Regiment, who they assumed had been captured without being able to flee.

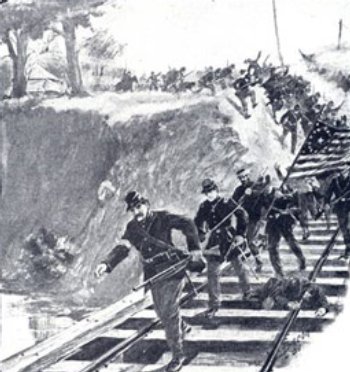

The Very Last Vermonters to Leave the Monocacy

Image from NPS Monocacy Battlefield stories page.

The very last Vermonters to leave their position on the Monocacy battlefield were those remaining from the 75 men who were part of the 10th Regiment detachment set up on the west side of the river guarding the railroad bridge. These men had been the first to engage the Confederates as they moved down the Georgetown Pike, and they were the last to leave as Union forces withdrew. Under severe pressure from advancing Confederate troops, these Vermonters had to flee by skipping from tie to tie on the floorless railroad bridge, since the Georgetown Pike bridge next to it had been burned by Union troops to prevent its use by the Confederates. The young commander of this detachment and the regimental national-flag-bearer were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their actions at the Battle of the Monocacy

Returning to Baltimore

On the morning of July 10th, the entire, reassembled Union command that had survived combat at the Monocacy marched eastward along the Baltimore Pike until they reached Ellicott's Mills (located at what is now Ellicott City). Here the combat-weary troops were fed by local loyal Union supporters. The men of the 10th Regiment, however, weren't able to rest long there, as David and his comrades were sent on to march six more miles to the Relay House (at the site of present-day Relay, Maryland).

The Relay House was at a junction on the B&O line where the track splits, with one line going south into Washington, the other north to Camden Station in Baltimore; the 10th Regiment probably had the mission of securing that junction. The next day, July 11th, they took the train to Baltimore, where they stayed for three days, presumably resting.

The men of David's regiment deserved a brief rest. They had been under arms for 70 hours, marching back and forth all day Friday in the mock defense of Frederick, marching down to Monocacy Junction Friday night, standing intensely in the line of battle all day Saturday, and marching in retreat for 40 miles back to Relay House south of Baltimore on Sunday, except for their brief train ride from Monrovia to New Market. And this was all with only meager rations left and in the midst of mid-summer middle Maryland's hellish heat and humidity.

On July 14th David Whitney's 10th Vermont Regiment, along with the rest of 6th Corps's 3rd Division,.were sent on to Washington to rejoin the 6th Corps for pursuit of the Confederate forces the 10th Vermont Regiment had helped stymie at the Monocacy.

Saving Washington at the Battle of the Monocacy

The Confederate forces that had come up the Shenandoah Valley in June 1864 and on down through Maryland in early July had an obvious mission: if not the actual capture of Washington—at least dealing a serious psychological blow to the Union cause with a massive assault on the capital city. The right turn they took at the city of Frederick was meant to get them along the Georgetown Pike to Washington while the capital was left without sufficient forces for its defense.

But the intense resistance the outmanned Union troops put up at the Battle of the Monocacy dealt serious blows to the Confederates in the amount of casualties they suffered and in the delay by a day of their advance on Washington. After that battle, while David Whitney and the rest of the Union survivors were moving eastward on July 10th away from the Monocacy along the Baltimore Pike, their Confederate foe was on their way down the Georgetown Pike into Montgomery County on the northern edge of Washington. The battle-weary Confederate soldiers rested that night by bivouacking around the cities of Gaithersburg and Rockville.

Early the next morning, Monday, July 11th, the Confederate forces continued their march on Washington and met little resistance until they got close to Silver Spring, where outlying Union pickets fired on the advancing Confederates but without halting their movement. By the time the Confederates reached Ft. Stevens, the Union's main fortification at the northern peak of the District of Columbia, the Confederate commander decided that his troops were too fatigued by the long march in the mid-July humid Washington-area heat to sustain any attack that day.

In the meantime, the rest of the Union's 6th Corps—from which David Whitney's 3rd Division had been detached and sent on steamships to Baltimore—arrived in the Union's capital on their own steamships after sailing up the Chesapeake and into the Potomac to the Washington waterfront. They were then rushed up to the opposite end of the city to Ft. Stevens where they set up a defense against the Confederate forces outside the gates.

There was some firing between the two forces, including, on July 12th, the shooting of a Union officer standing next to President Lincoln, who visited the fort briefly on that day and the day before. But by the next morning, July 13th, the Confederate Command gave up their plans to attack Washington and followed the Potomac River back up through Maryland to a place where they could cross back into Virginia.

Union forces did not follow immediately but did so before too long. David Whitney and his 3rd Division comrades soon rejoined the 6th Corps and participated in the pursuit of their foe from the Battle of the Monocacy in a campaign in the Shenandoah Valley that was to last for several months and take them into several more fierce battles.

The Fierceness of the Battle of the Monocacy

The Battle of the Monocacy was one brief but deadly battle. It lasted only one day, July 9th, 1864—from the first sign of Confederate movement around 7:00 in the morning until the last Union troops had withdrawn from their positions by about 5:00 in the afternoon—and was confined to a very small area along the banks of a tributary of the Potomac River. But on that day, the reported total of casualties between the two sides was set at 2,359. With about 1600 of that total, the Union forces suffered a little more than twice as heavily as the Confederates .

David Whitney's regiment—despite its exposed position on the Union's left flank of the fiercest parts of the battle and despite the fact that it was the last to leave the field—reported only three killed and 26 wounded, four of whom later died of their wounds. In addition, however, 32 men were reported missing, nine of whom later died in Confederate prisons.

The fierceness of the battle was perhaps best summed up in the after-action report forwarded to his corps headquarters by the commanding general of the Confederate infantry division that had made a frontal assault on David Whitney's division. In his description of what he called a "rare occurrence"—witnessed at a point near the river where Union troops had had to pull out while leaving their dead and wounded in the water and on the river banks, and where his own men had set up for their final assault—the Confederate general said there was such a "(p)rofuse...flow of blood from the dead and wounded that it reddened the stream for more than 100 yards below."

©2007 by Thomas Lee Eichman. All rights reserved.