The David Whitney Story

Part II – Chapter 5

David's Military Service

Section 11

Ending the South's Penetration of the North

Pursuing the Monocacy Foe into the Shenandoah Valley

Upon returning on July 14, 1864, to Washington, DC—after stalling the Confederate assault on the capital city at the Battle at the Monocacy in Maryland—David Whitney's 10th Regiment rejoined the rest of the Union's 6th Corps as it moved westward along the Potomac River. The combined forces of the 6th Corps, made up of the men who had survived that fierce battle in Maryland—along with those who had reached Washington in time to put up an impressive enough defense within the District at Ft. Stevens to make their foe shy away from another face-off—spent the next four weeks pursuing those same Confederate troops in the northern part of the Shenandoah Valley.

These Confederate troops had conducted an offensive north in mid-June 1864 that succeeded in thwarting a Union plan to destroy railroads, canals, and hospitals in Lynchburg, Virginia, at the southern end of the valley. The Shenandoah Valley, with its agricultural wealth, was an important source of supply and support for the Confederacy during the Civil War, and the Union Command had tried several times to take control, or at least prohibit the Confederate military from controlling the valley and its resources. The pursuit of their foe in mid-July by David Whitney and his 6th Corps comrades was part of this general concern.

On July 17th the Union contingent caught up with the Confederates in the northern end of the valley in Clarke County, Virginia, and attempted to control passage over the Shenandoah River in that area. But they did not succeed, as on the next day a Confederate division attacked the Union division that had arrived furthest downstream and held them immobilized until dusk .This set back the pursuit for several days, as the rest of the Confederate troops had managed to leave the area during the fighting.

On July 20th a brief surprise assault by Union troops at Rutherford's Farm in the adjacent Frederick County, Virginia, caught the Confederates in the midst of deploying there, causing them to retreat to the town of Winchester. The main Confederate forces then set up their primary defenses further south at Fisher's Hill, leading the Union Command to decide that the Confederate cause was over in the Shenandoah Valley. The 6th Corps and other units were ordered back to Washington to prepare to return to Petersburg and rejoin the Union siege of that city.

A Confederate Blow to Pennsylvania

However, on July 24th, the Confederate command launched an assault on the diminished Union defense at Kernstown on the south side of Winchester, causing a Union withdrawal north and across the Potomac River into Maryland at Williamsport. Then on July 30th, the Confederate cavalry unit that at the beginning of July had gained handsome ransoms from the Maryland cities of Hagerstown and Frederick, now had pushed even further north, across the Pennsylvania line to Chambersburg, where they set fire to many buildings when that city refused their demand for an even handsomer ransom, $500,000 in US currency, or $100,000 in gold.

Illustration courtesy of harpersweekly.com.

Chambersburg Buildings after Confederate Burning

As a result of this renewed Confederate activity in the north, the Union Command reconsidered the decision about sending the experienced combat troops back south and kept David Whitney's 10th Vermont Regiment and the rest of the 6th Corps in the northern sector of Virginia for further combat action in the Shenandoah Valley.

Finishing off the Confederate Threat to the North

On August 8, 1864, the union Command set up the Army of the Shenandoah and gave its newly appointed commander, a cavalry general, command over all the Union forces in the area with the task of driving Confederate forces from the valley and eliminating its economic value to the Confederacy.

For the first month many of the battles involved primarily cavalry units. On August 21st, in the battle of Summit Point near Charles Town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, David's unit was in formation at the end of the 6th Corps line that succeeded in delaying the Confederate pursuit of Union cavalry. At the Battle at Smithfield Crossing, that started on August 25th and took place through Jefferson and Berkeley Counties, West Virginia, the 6th Corps's 3rd Division, of which the 10th Vermont Regiment was a part, was brought in on August 29th to halt the Confederate infantry offensive that was forcing Union cavalry back along the road to Charles Town.

By the beginning of September, the Union forces had engaged the foe mostly in brief skirnishes. The Confederate Command had assumed that the Army of the Shenandoah was not a great threat and had spread their troops north of Winchester, Virginia, to Martinsburg, West Virginia in attacks against the B&O railroad.

On September 19th, the Union Command launched an attack on Winchester, Virginia, from the east along Berryville Pike but was somewhat slowed in arrivng there through narrow canyons and roads, consequently allowing the Confederate troops to regroup at Winchester. The 6th Corps was one of two corps that formed the main attack across the Opequon River and formed their assault line to the right of Berryville Pike.

As part of the 6th Corps, David's regiment charged through some woods and across an open field in the face of Confederate musket firing. Confederate divisions—units that David and his comrades had faced at the Monocacy—charged, initially beating back portions of the Union's assault, but eventually the Union troops were able to countercharge and drive the Confederates out of Winchester and back down to Fisher's Hill. The 10th Regiment, as part of this routing of the Confederates, felt vindicated in turning the tables on their Monocacy foe.

Image from Library of Congress Collection

The Battle at Opequon(The Third Battle of Winchester)

Both sides took many losses in this intense battle at the Opequon near Winchester, with David's regiment having 11 men killed and 42 wounded. Four men who were initially reported missing rejoined their comrades subsequently.After the defeat on the 19th, the Confederate forces set up a strong defensive position at Fisher's Hill, just south of the town of Strasburg in Shenandoah County, Virginia, which was south of Frederick County. On September 21st the Union forces, which had followed their foe down to Fishers Hill, advanced on these defenses and managed to gain important high ground. In the afternoon of the 22nd, David's regiment was part of a final rush at the remaining Confederate line and overpowered their foe, whose total defense collapsed. The 10th Vermont had one man killed and six wounded at Fisher's Hill.

The overwhelming power that the Union's Army of the Shendandoah demonstrated at Fisher's Hill led the Confederate Command to pull their troops a long distance further south to Waynesboro, in Augusta County, Virginia, between Staunton and Charlottesville.

With half of the Unon Command's assigned mission apparently completed—the elimination of the Confederate military as a force to reckon with in the valley—they proceeded to their second task, cutting off the supplies for which the Confederacy had relied on the Shenandoah Valley's rich farmland as a main source. For the next month the Union forces practiced a 'scorched earth' policy, destroying crops and burning barns, mills, and factories from Strasburg in the northern part of the valley to Staunton in the south. This was the forerunner of a similar policy carried out in November and December in the Union's march to the sea across Georgia from Atlanta to Savannah.

One Last Confederate Stand in the Shenandoah Valley

With the Confederate forces encamped in the higher mountains in the south Shenandoah Valley, the Union troops, including three corps and two separate cavalry units, had set up their camps along Cedar Creek in Frederick, Shenandoah, and Warren Counties at the northernmost tip of Virginia's portion of the valley.

In the middle of October, David's 6th Corps was initially designated to return to Petersburg on the assumption that the Confederates in the valley were sufficiently weakened to prevent them from attacking again. However, the Confederate Command did launch an offensive northward after planting a rumor that additional Confederate troops were coming up from Petersburg to reinforce their diminished units. The 6th Corps was recalled, and all the Union forces returned to the Cedar Ceek encampment with David and his 6th Corps comrades in the northernmost position of the Union line, west of Middletown, south of Winchester.

On the night of October 18th, the Confederate Command launched a surprise attack by moving part of their troops up the valley and around the base of the Massanuten Mountain to begin their attack from the south instead of from an easier route on the west side of Cedar Creek, as would have been expected.

At sunrise on the 19th, under heavy fog, the first Union troops that were struck by the surprise attack were those of the southernmost-positioned 8th Corps, who, after putting up a brief fight, broke and ran. Many were taken prisoner, a good deal of them not dressed for battle, having been caught off guard in their sleep.

The Confederates then moved on to the position of the next Union Corps, the 19th, and was joined in this assault by another Confederate division coming from the west. The 19th Corps broke also, with many of them scattering back across their own defenses.

That left only David's 6th Corps, who put up a vigorous defense and, though withdrawing, managed to slow down the Confederate advance, something the 10th Regiment was good at, based on their previous experience against these same forces at the Monocacy.

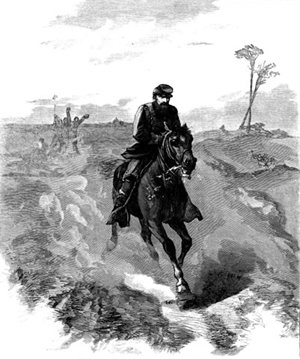

As Union forces were withdrawing to Middletown, word got back to the Union commanding general, who had been in Winchester overnight. He came racing on his horse toward Middletown and arrived at the battlefield later that morning.

General Sheridan Races from WinchesterDuring the Battle at Cedar Creek

Illustration courtesy of harpersweekly.com.

The Confederate Command misjudged the extent of their success and let up on their attack, thinking they had completely routed the Union defense from which they had taken more than 1000 prisoners and had captured 18 artillery pieces. But before the Union general arrived and reassembled his forces, David's 10th Regiment charged Confederates holding an abandoned Union artillery position and succeeded in recovering some of the Union guns that had been taken. They then were forced to retreat but did so in increments, continuously turning and firing as they moved back, certainly somewhat less than a rout.

Around 10:30, the Union commander starting rallying his subordinates, while Confederate troops, mostly hungry and exhausted from their overnight march and morning battle, were busy pillaging the abandoned Union Cedar Creek camps.

Around 3:00 in the afternoon, the Confederate command launched another, less massive assault; but by that time it was too late. The restored Union forces easily turned back the attack and by 4:00pm were launching their own counterattack. One Union cavalry unit joined the infantry in the offensive while other cavalry units cut off the Confederate escape route by destroying a bridge. Union forces captured hundreds of their foe and 48 guns—including the rest of the 18 that the Confederates had captured—and confiscated irreplaceable Confederate supplies.

David Whitney again survived one of the fiercest and most important battles of the Civil War, a battle like those at Gettysburg and at the Monocacy that turned the tide of the war in the Union's favor. In this day of combat at Cedar Creek, 15 members of David's 10th Vermont Regiment were killed, 66 were wounded, of whom nine subsequently died from their wounds, and four were reported missing.

Return to Petersburg

The Battle at Cedar Creek effectively ended the fighting in the Shenandoah Valley for David's 10th Vermont Regiment, but they remained in the valley through the month of November. On November 8, 1864, the Tuesday following the first Monday of the month, David, along with 194 other members of the 10th Regiment, voted for Abraham Lincoln for a second term as President; 12 of his regimental comrades voted for Lincoln's opponent, former Union General George McClellan. On the fourth Thursday, November 24th, the regiment celebrated Thanksgiving, feasting on turkey that had been sent to the Union army by citizens of New York City.

At the end of November, the 6th Corps was ordered to rejoin the Army of the Potomac for the final siege of Petersburg, Virginia. On December 3rd, David and the other surviving members of the 10th Regiment, as part of the 6th Corps 3rd Division, marched to the railroad station at Stephenson, Virginia, where they loaded into crowded freight cars for transport to Washington.

Early in the morning of December 4th, they set sail from Washington on a steamer down the Potomac, then back down the Chesapeake Bay and up the James River to City Point where they arrived later that day. They continued on to Petersburg via one of the the Union military railroads that had been set up during their absence from that area.

Wharfs at City Point (Hopewell), VA

Image from National Archives Collection.

Depot of the Union Military Railroads

This voyage on the Chesapeake and the James retraced in reverse a portion of the water route that had taken them to Baltimore in July.

When David Whitney arrived back in Petersburg, it was the beginning of the end of the Civil War. The Union's success with the 'scorched earth' strategy in the Shenandoah Valley was being repeated in Georgia, and Union forces around Petersburg were building significant fortifications in peparation for a final assault.

The day David returned to Petersburg, that very day, December 4, 1864, was also the beginning of the very end of life for one of the members of his family. In South Carolina, in the aftermath of a maneuver that was meant to support the consequences of the 'scorched earth' offensive in Georgia, David's brother Alonzo was shot by his own troops and died from his wound the next day, December 5, 1864.

©2007 by Thomas Lee Eichman. All rights reserved.