The David Whitney Story

Part II – Chapter 5

David's Military Service

Section 12

Return to Petersburg

David's Last Battle

Digging In and Waiting It Out

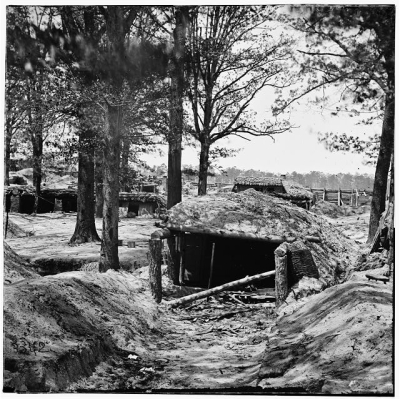

Upon their return to the Petersburg, Virginia, area, in December 1864, David Whitney's 10th Vermont Regiment took up a position with the rest of the Union's 6th Corps along the Weldon Railroad on the southeast side of the city. While the men of the 6th Corps were away in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and the Shenandoah Valley, the Union Command positioned their forces to build trenches and fortifications in preparation for a final siege of Petersburg. The aim was to drive Confederate forces from the Richmond area.

Petersburg Trenches and Fortifications

Image from Library of Congress Collection.

The men of the 10th Regiment settled down into camp life, sleeping initially that cold December in tents but keeping busy building more permanent quarters between shifts on guard duty and picket duty. This must have offered some relief from the extensive series of battles they had experienced starting in May with the Overland Campaign moving south to Richmond and Petersburg and extending into the important battles from mid-summer into late fall that considerably lessened the Confederate threat back north. During the previous eight months David's regiment had marched long distances, but now they could stay in place for a while and wait out the start of the final siege.

Face to Face and Voice to Voice

The men of David's regiment were no strangers to camp life, most of them having served in units guarding Washington from camps in northern Virginia in late 1862 into 1863 before the battle at Gettysburg and again early in 1864 before the start of the Overland Campign. One of the hazards from their previous encampments was present here too, disease. A few of the men in Company G got mumps in mid-January and then early in March and other diseases also. Something new that gave them caution was the close proximity of their picket line to that of their Confederate foe.

Out on the picket line, David and his comrades often faced off against their confederate picket-duty counterparts without much firing of their weapons but within easy shouting distance of each other. Once in a while the one side would whistle and the other side would whistle back. Once at midnight confederates asked the men of Company G if they had a lot of hardtack, a simple biscuit or bread made of only flour and water that soldiers often carried with them on the frontline. Company G men in return invited them over to their side to see but got no further response.

Another time one man from Company G went up to the Confederate fence, grabbed a fence rail, and took it back to the Union side without interference from the other side. And one morning, just before dawn, somebody from one side crowed like a rooster. This was followed by others joining in with raucus noises of more crowing plus dogs barking, sheep bleating, and whatever kind of loud sound they could produce. Company G thought this was fun for a change. But in store for both sides was much more serious noise-making with consequences that were other than fun.

Crossing the Lines

In late March, the number of Confederate deserters coming across to the Union lines began to increase, and the frequency of desertions was high enough to easily keep the 10th Regiment on picket duty awake all night. For example, one night six Confederates came across to give themselves up to the 10th Regiment, and another morning ten more passed through on their way to surrender. Those deserters that brought along their weapons and turned them in were given a bounty of $30 each.

The Confederates who did cross Union lines maintained that for every one of them who did so, five more were deserting and returning to their homes in the South. The prospect for a more general surrender soon seemed more real to the men of David's Company G as the number of men and weapons available to the Confederate cause continued to decrease.

Confederate Assault on Fort Stedman

By the end of March 1865 Confederate forces were taking heavy losses in the Carolinas and the Shenandoah Valley was essentially closed down by Union forces. The Confederate Command decided to try a surprise attack on the Union build-up in the Petersburg area with the hope of effecting an orderly Confederate withdrawal from the Richmond area.

Early in the morning of March 25, 1865, about one half of the Confederate forces in the area attacked Fort Stedman on the northeast portion of the Union line. This position the least fortified wooden obstructions to its front and was close to a supply depot on the Union's military railroad connecting to the Union command and logistical center at City Point.

Interior of Fort Stedman

Image from Library of Congress Collection.

On the night before, David and 230 others of the 10th Vermont Regiment were out on the picket line at the front of their parent 3rd Division of the 6th Corps. The first wave of confederates, starting at 4:00am, overran and captured the fort and supporting artillery batteries and took almost 1,000 Union troops prisoner in the process. But Union forces, including the 10th Regiment, counterattacked and were able to put an end to the Confederate success. In this counterattack, the 10th charged from the left and took 160 prisoners and their guns and equipment.

David and his comrades played a significant role in the Union counterattack because of how they handled their defensive position during the initial attack by the Confederates. The 10th Regiment was part of a charge over open ground to the front that was meant to engage the oncoming enemy assault. As other Union regiments halted and some retreated in the face of the onslaught, the 10th Regiment halted and fell to the ground, holding that position while other pickets generally fell back to the original line.

After pulling in more troops as reinforcements, the Union counterattack began, moving forward to the ground the 10th was holding. When the other Union skirmishers reached the 10th's advance position, David and his comrades lept up and double-timed forward with loud cheering, storming the trenches where the Confederates had halted, overtaking them without firing a shot until they reached the trenches. It was here that the 10th took prisoners.

Although there were numerous casualties in this battle, the hardened veterans of the 10th Vermont Regiment suffered only two losses. Their contribution by holding the ground in the face of overwhelming opposition was similar to the one they had made in the battle of Cold Harbor the previous June. It also was reminiscent of the role they played at the Monocacy, when they held their position there in the face of overwhelming odds until the very end, being the last Union unit to leave that battle.

The Final Siege

A severe Confederate loss southwest of Petersburg on April 1 cut off the best Confederate route out of the Richmond, the Southside Railroad, and marked the beginning of the end for the Confederate cause. That night, the Union Command assembled their troops facing across from the Petersburg defenses in formations ready to charge the heavily fortified Confederate trenchesThe men of the 10th Regiment had just gone to bed when artillery fire broke out in the distance to their right. They were ordered to get in formation in their defensive trenches in anticipation of combat.

Union Soldiers in Petersburg Trenches before Battle

Image from National Archives Collection.

Between 11:00pm and midnight, the men were served coffee, and then moved out to a position in line just behind the Union pickets, about 200 yards from the Confederate pickets facing them.David and his comrades remained in this position in the cold darkness for another 3-4 hours while musketeers among the pickets sporadically exchanged volleys of bullets. During a lull in the firing, one of the Confederates yelled, "Haloo, Yanks. Guess it's nothing but an April Fool after all." Not letting this barb go unanswered, a Union picket replied, "Not so much of an April Fool as you may think," upon which the exchange of metallic barbs began again.

Around dawn on April 2, the Union's 6th Corps was ordered to charge the Confederates entrenched in Fort Welch immediately to the front. The Corps' 3rd Division, which included the 10th Regiment, made up the foremost line of the formation and led the way toward a strong earthwork protected by a deep ditch and behind which were six artillery pieces. The men of the 10th lept into the ditch, with some mounting the high wall while others jumped over the lower walls to the left and right.

Once inside Fort Welch, the 10th regiment found resistance to the right but swarmed the open position and took several prisoners. The remaining Confederates then gathered at a position where two artillery guns were being re-aimed at Union troops inside the fort. But a battle line formed by men from the 10th and joined by other Union troops who had just arrived advanced on the artillery position and managed to clear it of the Confederate artillerymen.

After regrouping, the 10th Regiment and other 6th Corps troops pushed on across a ravine and some swampy ground toward another, stronger Confederate entrenchment, which they overtook, capturing 100 of the defenders there. Other defenders remained in the woods nearby and put up a fierce struggle, firing their muskets and holding back further Union movement. Confederate reinforcements then assaulted and retook the fort.

In response to the Confederate assault, on of the 6th Corps artillery batteries was drawn up and started shelling the fort's occupants. before long, the Confederates completely abandoned Fort Welch, a phenomenon that was happening more generally in the Confederate Petersburg defensive fortifications.

The Fall of Petersburg and the Pursuit up the Appomattox

After the victory at Fort Welch, the 10th Vermont Regiment rejoined the rest of the 3rd Division as the 6th Corps marched toward Petersburg. The division stopped that afternoon within about two miles of the city. Later David's regiment, along with the rest of the 1st Brigade, moved on forward from this position. That evening they took over a line that had been abandoned by Confederate pickets in front of an important position between Fort Lee and the Petersburg lead-works and bivouacked there for the night.

Early on the morning of April 3, the 6th Corps' 3rd Division marched through the evacuated lead-works and soon joined in on the general pursuit of the Confederate Command up the Appomattox River, leading, after another battle on April 6th, to the surrender of the Confederacy Command at Appomattox Court House three days later, thus formally ending Ameica's only war of internal rebellion

Among the Surviving

During his service with the 10th Vermont Regiment, David Whitney had survived much bloody combat in which many of his comrades were either killed or wounded, including the battles in Virginia at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Cedar Creek, as well as the strategically very important battle at the Monocacy in Maryland, Before the final siege of the city of Petersburg, 82 men from the 10th Vermont had been killed in action, 317 were wounded, of which 49 died of their wounds, two had died of accidents, and 36 who had been captured in combat died in Confederate prisons.

In the final siege of Petersburg the 10th Vermont had the honor—though a rather deadly and not necessarily highly sought-after honor—of being the first to plant their flag inside Fort Welch. As a result of their heroic efforts, one man of the 10th Vermont Regiment was killed, 39 were wounded, nine of those dying later, and two were missing and unaccounted for. Among the wounded, though surviving, was David Whitney; he had taken a Confederate bullet in his leg. David's time on the line with his veteran comrades was now finished.

Bullet Taken from David Whitney's Leg Wound

Photo by Thomas Lee EichmanBullet courtesy of Duane WhitneyDavid Whitney's grandson

©2007 by Thomas Lee Eichman. All rights reserved.