The David Whitney Story

Part II – Chapter 5

David's Military Service

Section 3

A Great Battle at Gettysburg

Joining the Army of the Potomac for Duty at Gettysburg

On Tuesday, June 23, 1863, the 15th Regiment—along with the four other Vermont Regiments making up the Second Vermont Brigade, all nearing the end of their nine-month voluntary enlistment—were detached from the 22nd Army Corps in the defense of Washington and reassigned as the Second Brigade of the 3rd Division, 1st Corps of the Army of the Potomac. On the afternoon of June 25th, the brigade left Union Mills in Fairfax County, Virginia, on a long march north to join the rest of the Army of the Potomac for the coming battle at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Crossing Northern Virginia into Maryland

That first night the Second Brigade bivouacked in a hard rainstorm just beyond Centreville and then the second night at Herndon Station, both still in Fairfax County. On the third day, the Fifteenth Regiment became the rear guard for the brigade, providing protection for the others, especially the accompanying animals, supplies, and ammunition, as they proceeded up to a crossing on the Potomac River. Late that day, David and his Second Brigade comrades used pontoons to cross at what is now White's Ferry in Montgomery County, Maryland, and then set up camp near the town of Poolesville.

North to Frederick

On the morning of June 28th the Second Brigade began its march across Maryland, heading around Sugar Loaf Mountain and then north towards Frederick. On the way, most of the men got rid of their extra clothing and blankets to make their load lighter in the humid heat of a typical Maryland summer. They stopped that night short of Frederick and camped along the Baltimore and Ohio railroad tracks just north of Adamstown.

After arriving in Frederick the next day in the midst of a steady, daylong rain, the Brigade rested for three hours. At this point, the troops had been marching for four days and felt the effect on their feet. In an apparent economic decision, the chief quartermaster, the officer in control of supplies, had decided that those volunteers who were very near the end of their nine-month enlistment should not be issued new boots. Most men's feet were blistered and bleeding, and 90 members of the Brigade were left at Frederick, unable to continue the march to battle.

On toward Pennsylvania

In the afternoon, the Second Vermont Brigade continued northward from Frederick and camped that evening at Creagerstown, MD. The next morning, June 30th, they slogged through more mud on the way to an overnight bivouac at Emmitsburg, just three miles short of the Mason-Dixon line: on the other side, in Pennsylvania, was Gettysburg, only 10 more miles away.

During the six days of their march across northern Virginia and the state of Maryland on their way to Pennsylvania, David Whitney and his fellow Vermonters had covered 120 miles. They actually took one less day to arrive at their destination than the rest of the First Corps.

Joining the Battle at Gettysburg

The next day, Wednesday, July 1, 1863, just before combat broke out on the first day of the Battle at Gettysburg, the Second Brigade, as part of the 3rd Division, was ordered to leave the encampment at Emmitsburg and join the rest of the 1st Corps for the ensuing battle at Gettysburg. For this portion of the march, the 12th and 15th Vermont Regiments were separated from the rest of the brigade and assigned as rear guard for the corps train.

The Second Brigade, minus the 12th and 15th regiments, reached the battlefield early in the afternoon, but the Corps train, with its wagons and teams guarded by the 12th and 15th Regiments, moved more slowly on muddy roads caused by a late morning rain.

About five miles short of Gettysburg, the train halted in some woods, anticipating camping there for the night. However, the Union's 3rd Corps, which had diverted to the Emmitsburg Pike from movement along a route further to the east, came upon the train at that point. The 3rd Corps commander ordered the 1st Corps train to take another road, guarded solely by the 12th Regiment, and had the 15th proceed to the battlefield with his unit.

In the Midst of Battle

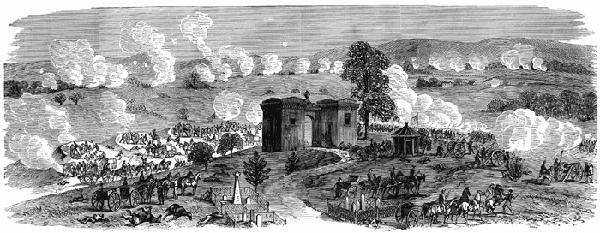

The next morning, July 2nd, the Vermonters awoke on the second day of battle to the sound of cannon fire from the Union artillery batteriy positioned on Cemetery Hill. At 9:00am the Second Vermont Brigade was ordered to a position to the right in support of the artillery until 11:00, when the 13th Regiment was moved directly behind the battery. At that point, the 15th was directed along the skirmish line in front and proceeded to the extreme left.

Image courtesy of FCIT Clipart Collection.

Cemetery Hill, Thursday, July 2

At noon, the 1st Corps Commander, alerted to possible Confederate cavalry raids on his supply train, ordered the 15th to return and reinforce the 12th Regiment in their guard duty. The 15th set off to return on the route it had come in to battle on, which took them between the line of battle and the skirmish line of the 3rd Corps in front of Little Round Top. The 3rd Corps staff, however, warned the 15th's commander of the hazards of continuing on that route: Confederate lines were not far down the projected path across a field towards Emmitsburg Road.

The Regiment was then ordered to go to Rock Creek Church, not far from the battlefield, where the 1st Corps supply train and the 12th Vermont Regiment were located. To get there, the 15th passed between Little and Big Round Top Hills and experienced the beginning of the fierce battle at Little Round Top, announced by preliminary artillery fire as David Whitney and his comrades were crossing the ridge between the two hills.

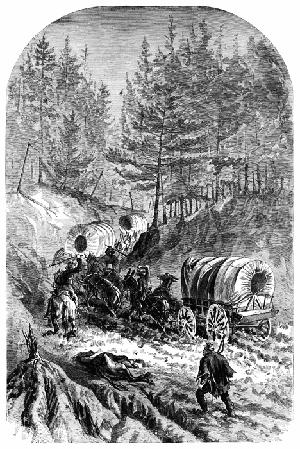

Image from Library of Congress Collection

View from Little Round Top to Big Round Top

That afternoon, the 15th Regiment found the supply train along Taneytown Road and stayed there overnight. The next morning, the 12th and 15th regiments set off with the supply train for Westminster, although two companies from each regiment were left behind to guard the 3rd Corps ammunition supply that was retained closer to the battlefield.

The Aftermath in Maryland

The 12th Vermont Regiment, whose enlistment expired on July 4th, was sent by rail to Baltimore as the guard for 2,500 Confederate prisoners captured at Gettysburg, and then from Baltimore on back to Vermont. But the 15th Regiment continued serving in Maryland for two more weeks.

Still guarding the 1st Corps wagon train, the 15th stayed in Westminster until Monday, July 6, when the train left in the morning during a hard rain storm on their way to rejoin the rest of the 1st Corps. After two-and-a-half miles, however, when they were warned again of Confederate cavalry operations nearby, the train stopped in the woods and waited until dark. Then, with David's Company and one other 15th Regiment company acting together as the advance guard—clearing the way through the mud and the woods—the train proceeded another 14 miles until stopping at 3:00am to catch some sleep. They set off again Tuesday morning for Frederick and arrived there in the afternoon, having traveled a total of 31 miles in 15 hours over a stretch of two days.

Image courtesy of FCIT Clipart Collection.

Supply Train

On Wednesday, July 8th, David Whitney and his 15th Regiment comrades moved across the Appalachian Trail near South Mountain and into Middletown, while the 13th Vermont Regiment, at the end of their enlistment, left for Vermont. On Thursday, the 15th Regiment was relieved of wagon-train guard duty and was ordered to join the rest of the Second Brigade.

Joining the Pursuit

The 15th Regiment then moved out on its way toward South Mountain where the rest of their brigade was bivouacked overnight. It was dusk before they reached the summit, and they had to search further in the dark for a while before coming upon their brigade comrades on a steep stone ridge. Those men were setting up stone fortifications to guard against possible attack, and the men of the 15th joined in. But the Second Brigade did not stay there long enough to need protective walls.

Early the next morning the pursuit of the Confederates resumed. The brigade marched as far as Boonsboro, where the sound of artillery fire signalled that armed conflict was still going on. But the Union forces managed to keep driving their foe backward as far as the outskirts of Hagerstown, where the Confederates halted and began to hold ground.

Both sides were holding their positions in place for the next day and a half with skirmishing going on between them. On Sunday the Confederates resumed their withdrawal, and the 15th Regiment and the other Union forces resumed their pursuit. After a brief Confederate halt at Funkstown on the south side of Hagerstown—answered by Union artillery shells—the race towards a Potomac crossing continued the rest of the day.

By late afternoon the Confederates had reached the vicinity of Williamsport, where at about 7:00pm the Union forces found them dug in. After some skirmishing by sharpshooter snipers, the 15th Vermont Regiment settled in for the night at the center of the second line of battle in front of the Confederate position.

The next morning, Union troops including David's 15th Regiment advanced on the Confederate entrenchment but found their foe had apparently slipped away in the night. The Confederate movement could be heard in the distance, and the Union forces gave chase. However, the Confederates reached their river crossing at Wlliamsport, and the Union forces gave up the chase, remaining on the Maryland side of the Potomac.

Homeward Bound

With their nine months of contracted service now ending, David Whitney and his 15th Regiment comrades marched back down along the Potomac River and on Saturday, July 18, headed home, departing the Maryland shore of the river via rail from Berlin (more recently renamed Brunswick) eastward to Baltimore and then north to New England.

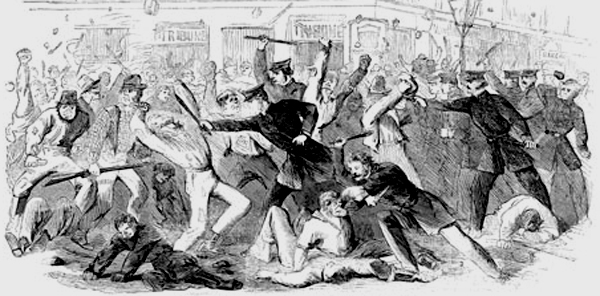

On the way back to Vermont, the 15th Regiment reached New York City in the midst of draft riots that had started after the announcement of a second draft and in reaction to the method of exemptions allowed under the draft law.

Illustration courtesy of harpersweekly.com.

New York City Draft Riots

Even though their term of service was officially over, David Whitney's regiment remained in New York for a short while until order was restored and then continued their journey home.

©2007 by Thomas Lee Eichman. All rights reserved.